Arts & Culture

RICH MULLINS HAD a museum of a personality. The singer-songwriter, who died in a car accident in 1997, loved to show off anything he found interesting, his friends say. From music to movies to the places he traveled, Mullins loved “for you to experience what he loved,” his friend and collaborator Mitch McVicker told Sojourners.And more than just about anything else, Mullins loved Jesus.

Mullins’ career tracked alongside the evolution of contemporary Christian music (CCM), which went from marginal in the 1970s to a powerhouse genre that sold a combined 31 million albums in 1996. Best known for the modern hymn “Awesome God,” Mullins wrote his fair share of songs that fit Christian radio. But more often, his music was a kaleidoscope of faith and humanity, offering a tour of human frustration and failure.

On “Hard to Get,” Mullins, as modern psalmist, asks God, “Do you remember when you lived down here, where we all scrape to find the faith to ask for daily bread? / Did you forget about us, after you had flown away?”

In other places, Mullins plays minor prophet. “I wrote this for the Religious Right,” he declared before singing that Jesus “came without an axe to grind [and] did not toe the party line,” during a performance of “You Did Not Have a Home.”

“CENTER THE CLAY.” I had one task for class and three hours to complete it.

Take two pounds of raw potential. Place it on the potter’s wheel. Use the strength of your hands and forearms to force the clay into balance.

For the full three hours, I failed. Unable to find the calm point of pressure to rest my human musculature between the universe’s centrifugal and centripetal forces. The clay fought back. It bucked and shimmied, slid and skidded. I pushed and pulled.

The teacher said, finally, “This clay does not yet want to be a bowl. You have not shown it how.” A gentle correction that expertly undermined my fixation with “the primacy of the real,” as French philosopher Gaston Bachelard calls it. Really, shouldn’t I be able to subdue this clay?

In the beginning, Ruth Handler created Barbieland. And Ruth said, “Let there be pink,” and there was pink.

Both films are sympathetic to creators, but neither film lets their creations off the hook. Oppenheimer worries aloud how the nuclear power he unleashed will shape the atomic age. Barbie faces a lunch table of schoolgirls who tell her exactly how the Barbie beauty standards made them feel un-feminine. But both films ultimately move beyond the myth of the single creator and focus on the forces that shape that creation’s ongoing impact on the larger world.

Musician Derek Webb, who started out with the band Caedmon’s Call in the 1990s, has “spent a career gnawing on the hand that feeds me in the evangelical Christian world,” he told Sojourners. From his time in Caedmon’s Call to his work as a solo artist for the past 20 years, Webb has outlined a winding and vulnerable journey of doubt, love, grief, and freedom. Most recently, Webb has been reckoning with his evangelical past, writing what he calls his “first Christian and Gospel album in a decade.”

Shortly after former president Barack Obama released his annual summer playlist, this missive showed up at the Sojourners office emblazoned on stone tablets. We're publishing it here in full.

In this day and age, even a very good restaurant struggles to survive; thriving is a pipe dream. And in this way, the restaurant industry doesn’t sound so different from Western Christianity.

The authors tackle a variety of common questions around sex, faith, and the church: What does the Bible actually say about sex? What are Christian teachings on sexual pleasure? Is spiritual trauma from purity culture a real thing? And the million-dollar question: If I no longer believe in purity culture, how do I create a new sexual ethic that’s still rooted in my faith and values?

The Miracle Club, starring Maggie Smith, Kathy Bates, and Laura Linney, is itself something of a miracle: Despite being attached to a major star (Smith) and a compelling story, the film, directed by Thaddeus O’Sullivan, almost never came to fruition.

Lisa Montgomery, the first woman killed by the U.S. federal government since 1953, was executed under former President Trump.

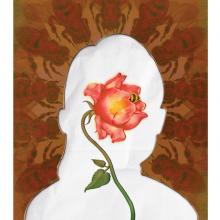

Red roses blooming all at once

when she finds between herself and any door

a male, be him grandson or lawyer, any flinch of any him brings a springtime

terror of thorn and attar, shivering with adrenaline, a clawing

of petal-flesh, the past beneath it, the blood

un-forgetting,

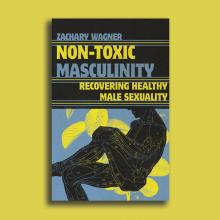

ENDORSEMENTS RARELY CATCH my eye, but some names that grace Zachary Wagner’s Non-Toxic Masculinity: Recovering Healthy Male Sexuality made my jaw drop. Amy Peeler and Kristin Kobes Du Mez — scholars renowned for tackling purity culture and male-centric theology — aren’t names you’d expect on a book like this. Most traditional Christian men’s thoughts on “biblical manhood” are not only flimsily dressed in culturally secular activities like playin’ sports and shootin’ guns, but also fatally based in unbiblical standards of hypersexual and violent behavior. Thankfully, Wagner swings over such pitfalls, laying out an expansive vision of masculinity rooted in the Jesus ideal: love for God and neighbor.

Wagner articulates how purity culture failed both women and men. “Many of the theological and cultural foundations of the movement were sub-Christian, even worldly,” he writes. “Dehumanizing theology leads to dehumanizing behavior” — behavior that includes fetishized virginity, body hatred, tolerated abuse, and sexual segregation. Purity culture, Wagner explains, calls men “animals” and “perverts,” confounding rhetoric I heard growing up in the church. This type of gendered, sexual denigration — especially when attributed, in part, to God’s design — only serves to further dishonor the imago dei of men and excuse sexual sin.

There’s a “pathetically low and impossibly high bar for masculine sexuality [that] trains men to resist, flee, and medicate (through marital sex) their untamable boyish immaturity rather than grow beyond it,” Wagner writes. The divinization of high libidos and heterosexual marriage can be doubly damaging for queer Christian men, who face additional stigmatization and erasure in the church.

ON A BRIGHTLY lit stage in Berlin, a performing artist drapes her dead son’s pajamas over her lap and begins to cry. She cries “loud and unabashed” until her ponytail starts to unravel, and her face becomes swollen and red. Soon, the audience begins to cry too.

The artist is Magos, mother to Santiago, the boy who dies in the opening pages of Gerardo Sámano Córdova’s novel Monstrilio. When Santiago dies, his parents — Magos and Joseph — begin to drown in their grief. But where Joseph isolates himself, weeping endlessly, Magos does something strange. She cuts out a piece of her dead son’s lung, leaves Joseph, and retreats to her mother’s house in Mexico City.

Part family drama, part queer coming-of-age story, Sámano Córdova’s debut gracefully wields its horror elements while navigating the complexities of grief. Structurally, the novel unfolds in four unique perspectives: Magos, Lena, Joseph, and M. After Magos learns about a folktale in which a dead girl’s heart grows into a young man, she sequesters herself in her mother’s house and feeds the lung pork and beef. She doesn’t clean or air out the room. Instead, she uses her odor as a shield, to keep her loved ones away from the lung, to protect its growth. This moment captures the overwhelming nature of Magos’ grief, but it also foreshadows the extent to which she will go to protect what she has left of Santiago.

Capitalist Cautionary Tale

BlackBerry highlights the role of greed in capitalism through the story of the rise of the BlackBerry smartphone. The film, which transports us to a time when smartphones weren’t omnipresent fixtures in our lives, shows the danger of valuing innovation more than ethics.

Elevation Pictures

THE WORD “SELFISH” is used many times throughout writer-director Laurel Parmet’s coming-of-age film The Starling Girl. Seventeen-year-old Jem Starling (Eliza Scanlen) hears it most often from her parents. Her father (Jimmi Simpson) uses the word to describe the period of his life before he got saved and gave up drinking. Her mother (Wrenn Schmidt) chides Jem for selfishness when she isn’t performing her duties at home. And at church, congregants direct the insult at Jem whenever her performance in the worship dance troupe pulls attention toward herself and away from God.

This understanding of “selfishness” dismisses the community members’ unmet needs. Jem, like most teenagers, is starting to consider what kind of person she’ll become. However, the only guidance she’s getting is from her fundamentalist church, which advises her to give up her dreams, fear her changing body, and let her church decide who she’ll marry. It’s no wonder that Jem’s thoughts turn increasingly to the only person who gives her positive, albeit problematic, attention: the youth leader, Owen Taylor (Lewis Pullman), the married son of her church’s pastor.

The Starling Girl is an empathetic portrait of the vulnerability and power of young women. It shows what can happen when the structures around them — family, church, patriarchy — limit that power and stifle their desires and dreams. This leads Jem to a sexual relationship with the similarly frustrated Owen, who’s drawn to Jem’s seemingly boundless potential.

AT THE CLOSE of the music video for “$20,” all three bandmates of boygenius — the young indie band turned chart-topping supergroup — cut their palms and swear a blood oath to each other. As I watched it for the first time, I couldn’t help but feel drawn toward prayer — is this what love looks like? It is subversive to hold on to the tenderness of friendships in a world rife with violence. But boygenius, consisting of Julien Baker, Phoebe Bridgers, and Lucy Dacus, refuses to do anything less in their debut full-length album the record — a searing homage to their love for each other. It is nothing short of divine.

Ringing with angst and affection, these songs meld post-grunge guitar riffs with heartfelt existential threads. In “Satanist,” they respond to ruminations in Ecclesiastes 1:2, “Everything is meaningless,” by singing, “If nothing can be known, then stupidity is holy.” By embracing the finitude and vapor of our existence, they, like the Teacher in Ecclesiastes, “[make] peace with [their] inevitable death” (from the song “Anti-Curse”).

Yet, amid all the nihilism, there’s joy. Boygenius’ gushing piano ballad “Letter to an Old Poet” nods to Rainer Maria Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet, in which the Austrian writer and mystic offers this instruction: “Believe in a love that is being stored up for you like an inheritance.” Boygenius finds this love in friendship.

IN THE SUMMER OF 2019, I fulfilled one of my childhood dreams: I cheered from the stands as the U.S. Women’s National Team won the FIFA Women’s World Cup in France.

This summer, I’ll be traveling to New Zealand and Australia to watch the team compete to win a third straight World Cup, a feat never before accomplished. I loved every moment of the 2019 tournament — the clutch penalty kicks and the cheeky goal celebrations — but two of my favorite moments came right after the final whistle blew.

The crowd of 57,900, which had been loud the whole game, got even louder.

The first chant was an easy and obvious way to cheer on the new champs: “USA! USA! USA!” I said it a couple times, but not with much gusto. It felt weird. If I said those letters, I wondered, what exactly was I cheering on? Just the team? Or also the U.S. president (at the time, Donald Trump) and his administration’s policies?

Fortunately, the chant shifted to one I could get behind wholeheartedly. As FIFA president Gianni Infantino, head of the international soccer governing body, walked to center field to begin the trophy ceremony, people around me started chanting: “EQUAL PAY! EQUAL PAY! EQUAL PAY!” Drummers behind the goal line punctuated the sound. Within seconds, the whole stadium had joined in.

At the time, a top-performing player on the U.S. Women’s National Team (USWNT) earned only 38 percent of what was earned by a top-performing player on the U.S. Men’s National Team. But as of 2022, the USWNT signed a collective bargaining agreement with the U.S. Soccer Federation that ensures that the national women’s team will be paid at the same rate for game appearances and tournament victories as the men. With this agreement, the U.S. team is setting a powerful global example.

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE IS all the buzz as I write this. It’s been impossible to ignore the omnipresent chatter about AI, from the deluge of online commentary to congressional hearings. As I thought about adding to the chatter — er, providing some insightful perspective from a progressive theological point of view — I wondered what more could be said. So, I decided to ask AI. I prompted Microsoft’s Bing AI chatbot to draft an essay, “from a progressive Christian perspective,” on the dangers of AI. The first line of the response: “As an AI language model, I am not capable of having a religious belief or point of view.”

Well, that’s reassuring.

Concerns about AI aren’t new — science fiction writers have painted grim pictures of machine consciousness at least since Samuel Butler’s 1872 novel Erewhon (wherein Butler wrote in his three-chapter “The Book of the Machines” that “there is reason to hope that the machines will use us kindly, for their existence will be in a great measure dependent upon ours; they will rule us with a rod of iron, but they will not eat us.” One hopes that we’ll find better reasons to hope.). Warnings of apocalyptic totalism abound: In May, Matthew Hutson wrote in The New Yorker, “In the worst-case scenario envisioned by [artificial-intelligence doomers], uncontrollable AIs could infiltrate every aspect of our technological lives, disrupting or redirecting our infrastructure, financial systems, communications, and more.”

Since the Bing chatbot is incapable of offering a theological perspective, I asked scholar Walter Brueggemann for his thoughts.

The Secrets of Hillsong, a docuseries streaming on Hulu, traverses some wide-ranging — and alarming — ground, detailing the international megachurch’s history of sexual assault allegations, affairs, child molestation, and cover-ups. In the midst of all this, it might be easy to gloss over something a little less flashy: what one might call, to put it mildly, an unhealthy volunteer culture.

In Asteroid City, Anderson buries ineffable grief under layers and layers of artifice.

Past Lives is a poignant exploration of both the burden and grace available to us as creatures of free will who are bound to the finality of our choices.