Arts & Culture

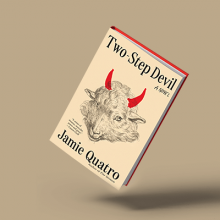

THE WORD “PROPHETIC” gets thrown around a lot in Christian circles. The adjective carries both an ancient heft and a forward-looking fire, the perfect jolt of biblical energy for the nouns that need it: a prophetic book, a prophetic sermon, a prophetic Instagram infographic. But living prophets, especially the self-anointed ones, aren’t so easily marketable. They’re stubborn and strange, somehow arrogant enough to believe they speak for an invisible God who turns out to be, more often than not, extremely angry at large swaths of humanity.

Two-Step Devil, the second novel of rising literary voice Jamie Quatro, places one such character in the contemporary South. Known simply as The Prophet, Quatro’s lonesome protagonist lives in the kudzu-entangled backwoods of northeastern Alabama, where he paints visions of impending holy war on junkyard scraps. He’s the kind of person who can “walk around behind the world’s curtain” — glimpse the spiritual stakes behind the drudgery of familiar, if fragile, social conditions. After rescuing a teenage girl from a sex-trafficking scheme, he’s confident he’s found the one who will deliver his apocalyptic message to the White House. While he’s frail and tormented by self-doubt, she’s young and, in his eyes, innocent. Meanwhile, the girl, Michael, must pull off an urgent mission of her own.

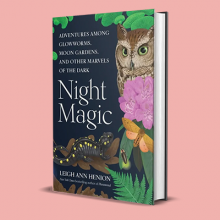

“LOOK FOR SHOOTING stars,” I texted my daughter who was working nights last August. After getting home around 3 a.m., she and her friend watched the annual Perseid meteor shower from our yard in rural Georgia. They saw a few faint streaks in the sky but nothing spectacular. Her friend was bleary-eyed and ready to go in, but Zora kept her eyes on the horizon. Then it happened: A streak of white with a smoky blue tail hurtled through the sky and took their breath away. Several years ago, my husband saw a similar meteor, one that lasted long enough for him to proclaim throughout its sparkly display, “Holy smoke!!!”

Meteor showers are not the only luminous rewards for those who walk in darkness. Leigh Ann Henion’s new book Night Magic (Algonquin Books) serves as both guide and advocate for honing our night vision and waiting long enough to be surprised. Synchronous fireflies, luminescent glowworms, and fragrant night-blooming flowers are among the many wonders illuminating Henion’s Appalachian nocturnal habitat

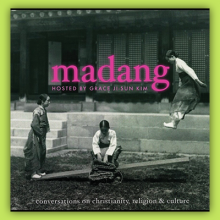

Living Room Theology

Hosted by theologian Grace Ji-Sun Kim, the Madang podcast features erudite conversations with scholars, ministers, activists, and more. Named after the courtyards found in traditional Korean homes, the show provides an inviting, intimate space to envision a more just world. The Christian Century

I WAS VISITING my sister and niece in Maine with my middle daughter when we learned that Dr. Bernice Johnson Reagon died. Our aunt in Oakland sent the obituary to our mom in Ohio, then Mom texted us: “Thought immediately of you both and all that she and her music meant to us. Long, lovely memories.”

Even in the news of her passing, Reagon, the founder of the celebrated music ensemble Sweet Honey in the Rock, was connecting women across generations, geography, religious, and racial categories. The music of Sweet Honey helped my mom, a white Quaker woman and Methodist pastor from rural Ohio, find her voice. It also shaped my sister and me as biracial Black women growing up in Washington, D.C. in the ’80s and ’90s. I took a course from Dr. Reagon during my senior year in high school. I never saw her again. Waves of grief and gratitude washed over me.

The day we got the news, we woke in a tent after camping near where the sun rises first over North America. As we drove past towering pine trees, taking in the news of one more passing — each death stirs up the sadness of all the other losses and more to come — my sister and I played our favorite Sweet Honey songs. We sang along to Reagon’s “I Remember, I Believe” from the 1995 Sacred Ground album: “My God calls to me in the morning dew / The power of the universe knows my name / Gave me a song to sing and sent me on my way / I raise my voice for justice, I believe.”

WHEN RAHIEL TESFAMARIAM was 5 years old, she and her mother flew from Eritrea to New York City, arriving in the United States with six-month tourist visas to help prepare for Tesfamariam’s eldest sister’s wedding. After the six months had passed, Tesfamariam’s mother began packing clothes for a return trip to Eritrea, but Tesfamariam adamantly refused to leave. Tesfamariam’s brother recalls being at the airport and watching their mother step to the gate; Rahiel stepped back and said, “Bye, Mommy.” And so it was: Rahiel Tesfamariam remained in the United States in the care of her siblings, out of the shadow of the Eritrean War of Independence, with an expired travel visa.

The rest of her story could be told this way: She became a legal permanent resident of the United States, graduated from Stanford University, became the youngest-ever editor in chief of The Washington Informer, received her Master of Divinity degree from Yale University, and launched Urban Cusp, an online community for Black millennials interested in the intersection between faith, culture, and justice. Tesfamariam worked as a columnist for The Washington Post; led #NotOneDime, a national Black Friday economic boycott during the 2014 Ferguson protests; and was named by Essence magazine as one of its “New Civil Rights Leaders.” She got married. She became a mother. It could be said that Tesfamariam pulled herself up into the American dream.

Tesfamariam’s book Imagine Freedom: Transforming Pain into Political and Spiritual Power (Amistad), released earlier this year, tells that story, but with a difference. Telling only that version, like the American dream itself, would be insufficient. Tesfamariam spoke with Sojourners associate editor Darren Saint-Ulysse in April about how she carries Africa within, political power’s ephemeral nature, and God’s command to free the captives. — The Editors

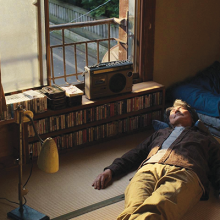

ONE WAY TO take a culture’s temperature at a given moment is to look at the art it produces. This is particularly true in film — a visual medium and a business largely driven by audiences’ perceived interests. Movies reflect their times, not just visually, but thematically.

Films made during the Great Depression, for example, included social realist dramas like Leo McCarey’s Make Way for Tomorrow, about an elderly couple who lose their home to foreclosure, and works of optimistic patriotism like Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, where Jimmy Stewart brings his determined charm to Capitol Hill. Others, like Capra’s romantic comedy It Happened One Night, offered troubled moviegoers good-natured escapism.

So, what’s on our minds recently, cinematically speaking? Among other things, a pandemic, corrupt institutions, international tragedies, and (another) contentious election year. There are many reasons viewers might want to escape into simpler or more fantastical worlds.

One recent trend, however, has surprised me: movies about presence.

DORCAS CHENG-TOZUN, author of Social Justice for the Sensitive Soul (Broadleaf), wanted to be an “unceasing voice” for social justice. “And while I was busy saving the world,” she writes, “I would also be the kind of person who’d happily sacrifice anything for a good cause.” But 10 months after Cheng-Tozun moved from the U.S. to China to set up an operations office for her spouse’s solar business, thrilled at the possibility of providing affordable electricity to billions of people, she experienced the “worst and longest panic attack” of her life. For more than a year, she could do “little more than sleep and cry and journal.” A crucial, difficult question arose: “Why can’t I handle what everyone else seems to be managing perfectly well?”

For Trish O’Kane, author of Birding to Change the World (Ecco), the breaking point was Hurricane Katrina, which destroyed her New Orleans home and neighborhood. “After a disaster,” O’Kane reflects, “you just can’t do as much. Nor should you. You need time to think, to ponder ... I needed a great slowing down.” She took up knitting, spent long hours outdoors on the ground “watching the clouds change shape and bumblebees loading their back legs with pollen and the yard birds going about their business.

Like Cheng-Tozun’s year of sleeping, crying, and journaling, these months surfaced life-changing questions for O’Kane. “I could feel my question changing,” O’Kane writes, “from What should I do? to How should I be?”

In their respective books, Cheng-Tozun and O’Kane write from the other side of activist burnout — something Cheng-Tozun experienced after working for multiple social justice organizations, and O’Kane after working in human rights journalism in conflict areas, both for many years. Both writers ponder how to change, heal, and move forward. Birdwatching was the gateway for O’Kane, while Cheng-Tozun found herself reflecting on sensitivity, introversion, and the many ways people are wired with different gifts to offer. They have different backgrounds and stories — Cheng-Tozun is now a writer and consultant who most recently worked for a Christian nonprofit that equips BIPOC contemplative activists; O’Kane is an environmental educator who created the “Birding to Change the World” program at University of Wisconsin-Madison — but both authors offer a similar invitation to those who yearn to make a difference: Learn to embody gentler, more sustainable ways of doing so.

NONVIOLENT DIRECT ACTION is a relatively new invention — though prefigured by the Cross, it was Gandhi, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., and a million others whose names we don’t know or remember who introduced this technique to us over the course of the 20th century. There’s no handbook for how it’s done, and no West Point equivalent — which means that we largely proceed by trial and error as we try to move the conscience of the world. We make it up as we go along. Which is fine, but you must be honest about what works.

Over the last year, one tactic that climate activists have tried is attacking cultural works — iconic paintings, right up to the “Mona Lisa,” and great shrines of humanity, most notably Stonehenge. They’ve been responsible, figuring out ways to do minimal damage, and perhaps such methods were worth a try: When you’re losing, you throw Hail Marys. And the people who carried out these actions clearly should not be subject to ridiculously punitive sentences.

THE LAST PICTURE in Richard Avedon and James Baldwin’s Nothing Personal, an exploration of American identity through the photographer’s eye and the essayist’s heart, holds a haunting some 60 years later. Two young boys look solemnly into Avedon’s lens. It is as if they stare into the soul of the watcher. It is as if in their innocence they wonder about the world in their silence. It is the children’s eyes that I can’t stop thinking about.

Their eyes are still our eyes, their gaze, still our gaze — weary, longing, determined, and despairing. Baldwin writes in the 1964 book, “Despair: perhaps it is this despair which we should attempt to examine if we hope to bring water to this desert.”

Baldwin and Avedon’s friendship and work together can be instructive for us because what we face as a nation is not much different from the Civil Rights years. We are presently dealing with a lack of trust; the forces of polarization are deepening within and without. There is, writes Baldwin, an “unspeakable loneliness” that we feel, wondering if anyone can feel what we feel and are angry about what we are angry about and are sad about what we are sad about. Then there is the kind of loneliness that takes root when “we live by lies.”

In this world where only the fittest survive, can a robot’s commitment to help without agenda possibly work?

Early in The Book of Belonging, a long-anticipated children’s story Bible, author Mariko Clark includes this paragraph: “Think about how cozy and special you feel when someone asks you about your day or wants to learn more about your favorite foods or hobbies. God made us to belong with God! That means God wants to be close and cozy with us. So all questions are welcome!”

The amber appears to ooze across the floor like slow-flowing lava. Containing found objects and materials sourced from Salvadoran communities around Los Angeles, Eddie Rodolfo Aparicio’s artwork is expansive and expressive of the materiality of often-marginalized Central American migrants in Southern California.

Following up his overwhelming victory in a rap battle with Drake earlier this year, and the news that he would perform at Super Bowl LIX next February, Kendrick Lamar dropped a surprise single last night, mentioning Christian rappers Lecrae and Dee-1 in the song.

Two queer pastors, Anna Blaedel and M Jade Kaiser, were having dinner together in 2017, when they posed a question to each other in the spirit of meaningful fun: What would it be like if they could create a public space for conversations about and liturgical resources for transformation, at the outer margins of Christianity and beyond?

The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power returned for its second season, bringing viewers back to a sprawling story inspired by the works of J.R.R. Tolkien.

In her forthcoming book, Films for All Seasons: Experiencing the Church Year at the Movies, Abby Olcese guides the church through the liturgical season via spiritual reflection on movies. Rather than tell readers how a movie is to be interpreted, Olcese guides participants on watching, considering, and discussing 27 films, each aligned with the liturgical calendar.

Loosely inspired by the experiences of Latoya Ammons in Gary, Ind., Netflix’s The Deliverance follows single mother Ebony Jackson as she battles demons, her past, and systems entrenched with racism and sexism — all to save her family.

Tia Levings made a decision for herself and her children on October 28, 2007. With the help of a priest, she planned for an escape from her abusive husband. “I heard a voice say, ‘RUN,’” she writes in her memoir, A Well-Trained Wife: My Escape from Christian Patriarchy.

THE VEGETABLES ARE trying to kill me. I am drowning in vegetables. I clock out of my home office, and there are the vegetables. I take weekend trips, come home, and there are the vegetables. I can’t sleep, because deep in the corners of my mind, the vegetables are there — slowly rotting, mocking me, blaming me for their inevitable demise.

This is not a horror movie. This is a CSA subscription.

Short for “community-supported agriculture,” CSAs provide subscribers a selection of farm-fresh seasonal produce every week. They are a sustainable and often cost-effective way to eat local and give back to your community. They are also a terrific way to spend hours chopping vegetables and Googling “kohlrabi.”

In the pre-pandemic years, I, a black-and-white-moral-thinking-trying-to-do-right no-matter-the-cost twentysomething, signed up for a CSA every spring. Rarely have I experienced more anxiety, more rage, and more helplessness than when faced with a brand-new “single-sized” (but still enormous) bag of produce while most of the previous week’s veggies remained untouched and rapidly softening. Yet I, ever the Good Consumer, stressed myself silly over produce season after season, because what choice did I have? I couldn’t destroy the planet.